AI Syllabus W1: What is AI?

Understanding deterministic and probabilistic systems in order to innovate in design

Table of Contents

Introduction

Why designers must understand system behavior before interfaces

Deterministic Systems

Definition

How deterministic systems are built

Examples of deterministic systems

Probabilistic Systems

Definition

How probabilistic systems are built

Examples of probabilistic systems

Why this distinction breaks UX patterns

Homework

Extra Resources

Additional reading

Interesting reads from the past week

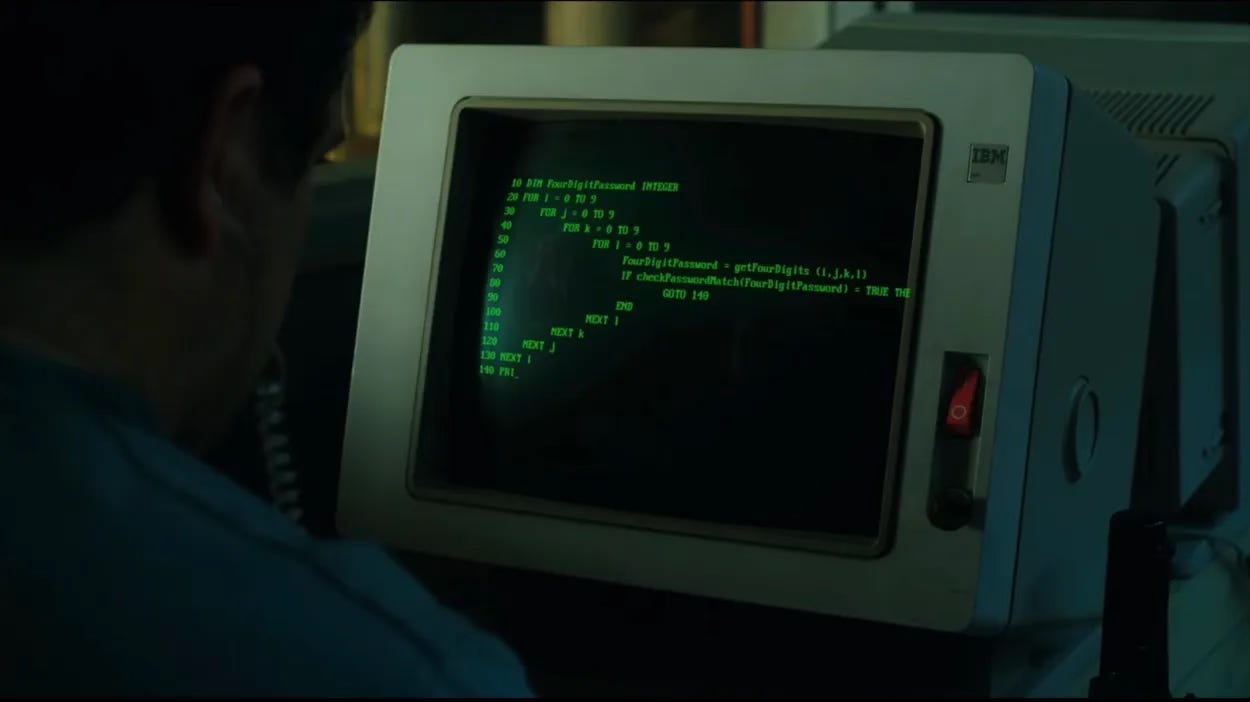

One night a few weeks ago, sometime around dinner time, I turned my once-every-few-days episode of Stranger Things (I’ve been rewatching the series since the finale aired). The episode that day happened to be the one where Joyce, Hopper, Mike, and Bob are trying to get themselves and Will out of a demodog flooded Hawkins Lab. In a heroic effort, Bob Newby SUPERHERO runs down to the basement to turn the power back on and reset the building security system by using BASIC.

If you’re not familiar, BASIC is a family of general-purpose, high-level programming languages designed for ease of use. “Ease of use” meaning ease of use for the times — to use some of the first desktop computers (microcomputers) you had to type in code, and basic was “easy.”

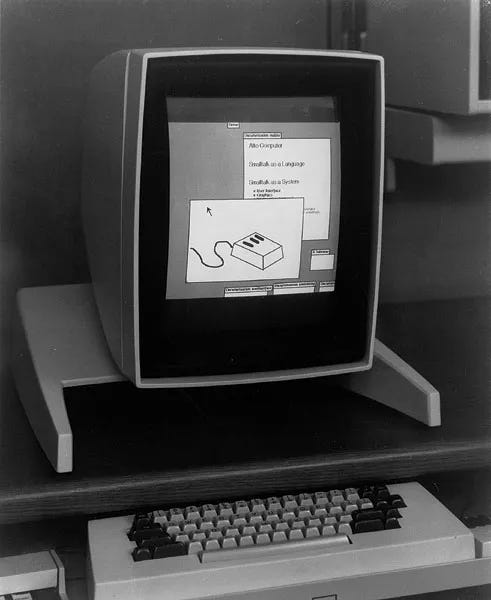

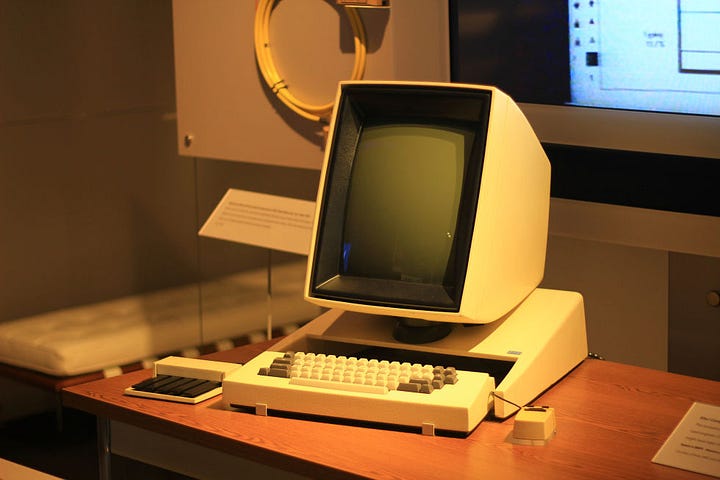

This reminder sent me down a rabbit hole of research. We all know the stories of Steve Jobs and his early UI innovations. The Macintosh was the first commercially successful desktop computer with a mouse and a GUI. Yes, it was the first instance of the modern GUI, but the words commercially successful matter, because the first GUI was actually introduced 10 years earlier.

In 1973, Xerox PARC released the Xerox Alto. It came with a steep price - $32,000 (equivalent to $140,000 in 2024) so it didn’t find much commercial success, as you can imagine. However, the Alto was the first computer system to introduce graphical elements that we still use to this day - a bit-mapped display, windows, menus, radio buttons, check boxes, and even a WYSIWYG text editor.

What’s wild to think about is that the people who came up with these elements literally had to come up with them out of thin air. Sure, the elements are simple and relate back to the real world which makes them easily understandable. But the first UX designers weren’t graphic designers, they were engineers. They innovated by understanding the system, not following a list of “best design practices.” Those didn’t exist.

We’ve been designing for the UI logic set in the 70s and 80s ever since. The Xerox team conceptualized it, the Apple teams set the standard. But today, for the first time since, we have an opportunity to innovate again.

Why Designers Must Understand System Behavior Before Interfaces

For decades, designers have been trained to work with deterministic systems.

UI and UX elements like buttons, forms, menus, error states, confirmations, and feedback loops were all invented for software that behaves in predictable, rule-based ways. You perform an action and the system responds in a straightforward and consistent way. E.g., if you click an X button you know that a window or tab will close. Every time you click it, again and again it will close. It follows the interaction logic from the BASIC times. Input, output, input, output. Over time, users learn this behavior with all elements and develop trust.

Artificial intelligence systems do not function this way. They violate this assumption at a foundational level because AI systems are probabilistic, not deterministic.

AI systems do not execute predefined rules, rather, their output is based on patterns learned from data. This completely reshapes what good user experience means and is the reason a lot of “bad UX” is prevalent in current AI products. We’re using interaction paradigms that promise deterministic behavior but deliver probabilistic instead.

That’s why in order to design good experiences for AI interactions, designers should first understand what kind of system they are designing for.

Deterministic Systems: Software as Explicit Instruction

Definition

A deterministic system is a system in which every output is explicitly determined by a set of predefined rules. It’s defined by its ability to produce the exact same output from the same input, every time it is executed, regardless of environmental factors.

Think of it this way:

Deterministic systems are like following a recipe. If you use the same ingredients in the same amounts and follow the same steps, you’ll get the same result every single time. There’s no randomness involved.

How Deterministic Systems Are Built

Deterministic software is constructed through explicit logic written by engineers. These systems rely on conditional statements, procedural flows, and clearly defined state transitions.

At a technical level, deterministic systems are composed of:

Conditional logic (if/then/else)

IF order total is over $50, THEN free shipping, ELSE charge $5.99.

Boolean operations (true/false)

Password matches database?

TRUE = access granted,

FALSE = “incorrect password” message

Fixed algorithms

Google Maps route calculation uses the same algorithm to always find the shortest path between two points given current traffic data.

Explicit error handling

If you try to access a page that doesn’t exist you will get a specific “Page Not Found” page instead of the site crashing.

Predefined constraints

If you try to write more than the 280 characters allowed on Twitter, the system won’t let you post.

The system does not generalize or interpret intent. It does not function beyond what has been coded and it has been “told” to do. If an unfamiliar situation arises for the system, it either:

Fails

Produces an error

Returns no result

This is by design.

Examples of Deterministic Systems

A light switch - Flip it up and the light will turn on. Flip it down, the light will turn off.

Submitting a form - If you fill out all the required fields and click the submit button, the form will submit. Every time you stumble upon a form, you’ll expect the same outcome for the correct input.

A combination lock - Let’s say you set the combination to 25-17-39. Every time you enter those numbers again, the lock will open. If you enter the wrong combination, it will stay locked.

Authentication systems -In order to log into your email account you need to enter your username and password. Assuming you entered the correct information, you will be logged into your email.

Probabilistic Systems: Software as Inference

Definition

A probabilistic system is a system that produces outputs based on statistical reasoning rather than predefined rules. Instead of executing explicit instructions, the system estimates the most likely outcome based on the input it received and its learned patterns.

Think of it this way:

Probabilistic systems are like rolling dice. Even though you’re doing the same action (rolling), you can’t predict the exact outcome. You know the possible outcomes (1 through 6) and in theory their likelihood, but each roll could be different.

How Probabilistic Systems Are Built

Probabilistic systems are created through training, not traditional programming.

Rather than writing rules like “If the user types X, return Y,” engineers need to provide the system with large data sets, model architectures, and optimization objectives. The system learns relationships between inputs and outputs by identifying patterns in the data it was provided with.

At no point does the model “understand” meaning of this data in the way humans would find “meaning,” it just learns statistical correlations.

At a technical level, probabilistic systems are composed of:

Statistical models

Spotify’s Discover Weekly analyzes patterns across millions of users and uses statistical clustering to predict what you’ll enjoy.

Probability distributions

Uber’s surge pricing system calculates distribution of likely demand at a certain time (e.g. after a concert) and adjusts prices based on probability curves, not exact rider counts.

Weighted variables

LinkedIn considers a combination of multiple factors like mutual connections, same company, similar job titles, location and weighs them to suggest users you should connect with.

Training data & pattern recognition

Autocorrect on your phone is trained on massive text datasets. It sees you misspell “teh” and recognizes the pattern matches “the” 99.9% of the time based on historical corrections. Who keeps writing duck…

Confidence intervals & uncertainty margins

Package delivery estimates are always given in windows of time based on historical delivery time variance and current variables because the system can’t guarantee an exact day.

This means:

There is no single correct output

Outputs exist on a probability distribution

Multiple responses may be equally valid

The system’s confidence is implicit, not guaranteed

Examples of Probabilistic Systems

A slot machine - if you pull the lever with the same force, same time of day, you will get different results each time.

Netflix recommendations - log into your account today and tomorrow at the same time and your “Recommended for You” might show the same titles with different cover pictures, show them in a different order, or even show you completely different titles.

Shuffling a deck of cards - shuffle the same deck of cards twice and you’ll get two completely different arrangements every time.

Social media feed ordering - every time you refresh Instagram, your feed order changes. Every time you do this, the algorithm is deciding what to show you based on your probability of engagement.

Getting a green light at an intersection - if you arrive at the same intersection at the exact same time of day on different days, the light might be red, yellow, or green depending on traffic patterns.

Autocorrect - If you type something like “I’m going to the…,” the next word suggestion will never be exactly the same. It changes every time based on your history, context, and probability models.

Why This Distinction Breaks Traditional UX Patterns

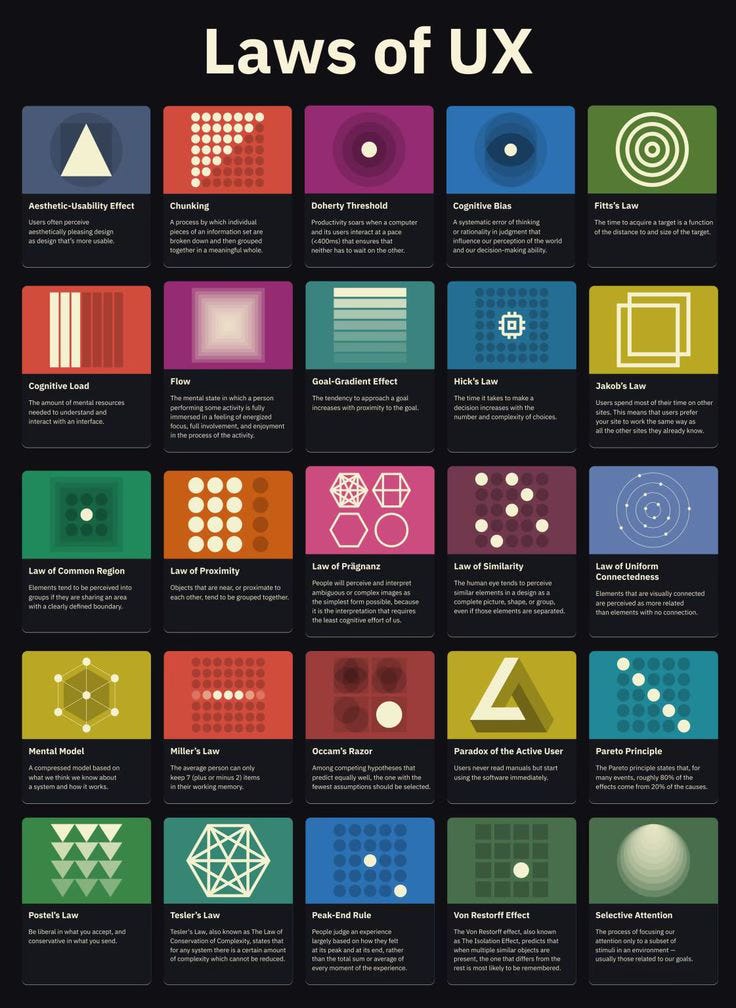

From the user’s point of view, deterministic systems create a stable mental model. Users learn that on any new system, actions are learnable and repetition leads to mastery because outcomes can be anticipated. And if you make a mistake, you can easily correct it by clicking an “Undo” button.

On the other hand, probabilistic systems feel flexible, adaptable, and currently mostly conversational. But this masks a lot of uncertainty, and a system may sound confident even when it is wrong. Unlike deterministic software, probabilistic systems do not naturally expose failure states. Those errors are one of the central design challenges of AI.

Traditional UX patterns work for predictability. These rules came out of observation of predictable user behavior towards the predictable system behavior. Making buttons “easy to find,” designing intentional error messages that appear only when a certain system rule is violated, these are all design rules that have been created through years of system consistency.

The key design assumption in deterministic software is that if a user performs the same action twice, they should get the same result twice. While most UX patterns we’re familiar with rely on guarantees, probabilistic systems don’t offer that.

This Week’s Homework: Redesigning for Probability

Now that you understand the difference between deterministic and probabilistic systems, it’s time to apply it.

Choose ONE (or all, if you’re feeling ambitious) of the three scenarios below. Each represents a real AI design challenge where traditional UX assumptions start to break. Create a design solution that acknowledges the probabilistic reality instead of fighting it.

Scenario 1: The Consistency Assumption

The Problem: You’re designing an AI writing assistant for a legal tech company that lawyers use to draft contract clauses. They’ve reported that “the AI keeps changing how it formats indemnification clauses.” Sometimes it’s a single paragraph, sometimes it’s broken into sub-clauses, sometimes it includes examples.

A traditional UX expectation is that consistency builds trust. But, in AI systems, consistency is not guaranteed and it’s not always wanted. Instead, coherence replaces consistency. The content is coherent (legally sound indemnification language), just not identical.

Your Challenge: Design an interface solution that reframes the expectation from:

“This will generate the exact same clause every time”

to:

“This will generate legally appropriate indemnification language that achieves your intent”

What UI elements, language, or interaction patterns help users trust coherence over consistency?

Scenario 2: The Binary State Assumption

The Problem: You’re designing a customer support AI chatbot for an e-commerce platform. Currently, the system shows only two states:

Green checkmark = “Issue resolved”

Red X = “Error — contact human support”

Users are reporting frustration because the AI often:

Answers part of their question correctly

Provides a helpful workaround, but not the solution they wanted

Gives an answer that’s plausible but needs verification

Understands their question but lacks authority to act on it

None of these fit under either “resolved” or “error.” Deterministic systems have clear success and failure states, while probabilistic systems operate in gradients.

Your Challenge: Design a status/feedback system that expresses the reality of AI responses. How do you show:

Partial success?

“Correct under one interpretation”?

“Helpful but incomplete”?

Confidence levels?

What can replace the binary success/error pattern?

Scenario 3: The Boundary Assumption

The Problem: You’re designing an AI-powered medical symptom checker. Unlike traditional form-based symptom checkers (which only accept predefined inputs like dropdowns), your AI accepts natural language.

This means users can type literally anything:

“my left knee hurts when i run”

“is this mole cancer”

“my dog ate chocolate what do i do”

“cure for immortality”

The AI attempts to respond to all of these, even when it shouldn’t. Deterministic systems enforce boundaries by rejecting invalid input. Probabilistic systems attempt to respond to nearly anything.

Your Challenge: Design guardrails that compensate for the AI’s lack of self-regulation. How do you:

Prevent the AI from answering questions it shouldn’t?

Redirect users when they’re outside the system’s scope?

Signal when an answer might be a confident hallucination?

Acknowledge the user’s input without providing dangerous advice?

What UI patterns create boundaries the AI itself cannot enforce?

Deliverable Format

Sketch it out, create a wireframe, or just write out your thoughts. If you’re up for a discussion, send your solution to me or drop it in the comments and let’s talk! I would love to see what you come up with.

Extra Reading

Additional Resources

NVIDIA — What Is Artificial Intelligence?

Towards Data Science — Deterministic vs. Probabilistic Deep Learning

The Art of Unix Usability — Chapter 2: A Brief History of User Interfaces

Medium — AI in Product Design Concepts: A Primer on Deterministic vs Probabilistic Systems

Interesting Reads from the Week

AI News

— Enterprise AI Adoption Shits to Agentic Systems

— Anthropic Selected to Build Government AI Assistant Pilot

WIRED — Why AI Breaks Bad

Tech Crunch — OpenAI launches Prism, a new AI workspace for scientists

Yahoo!Finance — Phoebe Gates and Sophia Kianni’s Phia raises $35M to ‘make shopping fun again’

Next week we will dive deeper into machine learning - understanding types of learning, when each is used, and how that affects user experience.

For questions, suggestions, collaboration, or consulting projects reach out to Jelena at hello@jelenacolak.com